This sermon was preached on the 24th of November 2024, the Feast of Christ the King, in the Anglican Parish of Kalamunda-Lesmurdie

Texts:

“If my kingdom belonged to this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews.”

Jesus uttered these words as he stood before Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. His hands were bound. His face was beaten and bloodied. He had not slept that night.

And so if Jesus is king, he’s strange sort of king, and his rule… his rule is a strange sort of rule.

Today we are gathered to mark the Feast of Christ the King. And yet we hear in the Gospel that the title of ‘king’ is not one that Jesus claims. It’s a title pushed upon him… pushed upon him by Pilate, and by the religious leaders who opposed Jesus… pushed upon him by those who wish to label him a rebel, swiftly put him to death.

Why then do we mark this feast? And if Jesus is king, then over what kind of kingdom does he rule over?

“If my kingdom belonged to this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews.”

The kingdom of Jesus does not belong to this world. It belongs to God.

It has no human being at its centre: its centre is found in God, Holy and Triune.

Three persons in eternal community, three persons who love one another continually, who offer themselves – all that they are – to one another, always and forever.

This is the character of Kingdom that Jesus proclaims. So no, he won’t summon his followers to burst in, to kick in the door, to scare off, to fight off, to kill the Roman centurions, to rescue him, to drive the Romans out of the Jewish lands. Instead he will go to the Cross, he will go the Cross and it is there that will make his ultimate proclamation of who he is, and who God is.

And this is the Kingdom that we are called to proclaim. We’re to model ourselves upon the example of Jesus, and of the Trinity… we are called to love God and to love neighbour.

This is difficult. The grace of God is a costly grace.

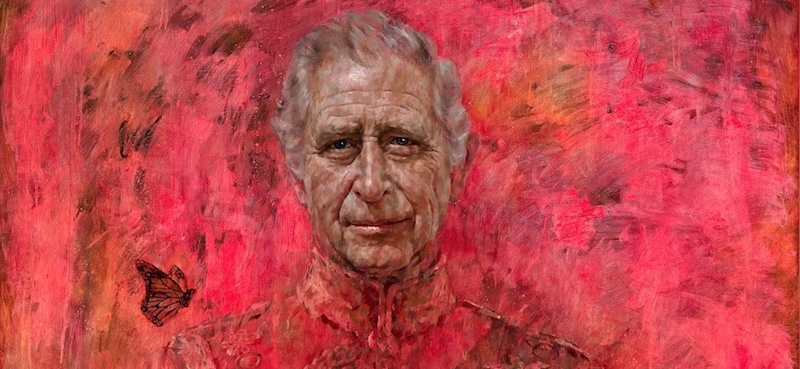

Take a look at this portrait of King Charles the Third, by Jonathan Yeo.

It was controversial when it was first unveiled: it was commissioned for the King, and unveiled by him. And dare I say, controversary is usually a good sign when it comes to art.

I’ll share what this portrait says to me.

The whole canvas is awash in red, the colour of the King’s uniform, the colour of blood. The king’s very face is ruddy with it, as are his hands, even as they grasp a sword.

And this bloody wash speaks to me of the sinfulness of human kingdoms, of the legacy of empire, of slavery, of whole people’s taken from their lands and put into servitude, of colonialism and dispossession, of domination and war. And Charles has talked about these things himself: he has said how difficult the history he has inherited as monarch is. And yet of all these things, he is indisputably the inheritor.

What should he do with that? Well this painting perhaps tells us something. If you like at it, at first, it could almost be a painting of Pontius Pilate. Of a monarch, bloody, awash in the consequences of sinful rule. And yet… take a closer look. look above the shoulder of the King.

A butterfly descends. A butterfly: a tiny, fragile creature, a creature that first emerges from an egg perhaps completely unnoticed, a little cluster of eggs laid upon a leaf. And as a caterpillar it feeds upon greenery, until one day it spins a cocoon, and disappears from sight, to emerge later a butterfly, and soar regal upon the winds.

A butterfly emerges from its cocoon as a creature so different that you could scarcely imagine that it came from that caterpillar. And surely this butterfly points to the ultimate hope of humanity: death, and resurrection. The story of Christ, the story of the world… indeed, the deepest Truth of the world.

And this is the story that we ourselves are drawn, bodily, into through the sacraments of baptism and holy communion. And so to my mind that butterfly, that butterfly that you could almost miss, is a figure of Christ: and in its descent upon King Charles, even as he is awash in all of the history of his role, good and bad, we see the hope of the death and resurrection.

And we do look for that: we look for our own death and resurrection, our own renewal, and we look for the death and resurrection of the institutions of our society, as God’s justice and the Kingdom breaks into the world.

That tiny, fragile creature proclaims possibility of freedom from sin; the possibility that the wrongs of the past might be mended. If you think about it humanity hands trauma on from generation to generation. Conflicts within our families, conflicts within our society, conflicts between different groups of people, identified by race or religion, ethnicity… we can think perhaps of many examples of these that we have encountered in our own lives.

This portrait tells us that if we embrace the kingship of Christ, then that cycle of violence and trauma, generation to generation, can be finally interrupted. We do not have to perpetuate the sins of the past.

So I’m moved that Charles accepted this portrait, with its complexity and ambiguity, and with the deep challenge it poses to him personally as our monarch. May God bless him and keep him, and may his rule be guided by the life and witness of Jesus Christ.

We proclaim Jesus. Jesus an unlikely king: a king who founded his kingdom not upon domination, but upon love and self-sacrifice. Through his life, death, and resurrection, Jesus proclaimed to us in the most perfect way who God is.

And now we stand at the end of the church year on the cusp of advent, we look ever for the return of Jesus. And we work together to build up the Kingdom.

It’s a daunting task. But we can do it, we can play our part, for we are made in the image of the God that Jesus proclaimed. Through God’s grace, we can embrace that image, and grow ever closer to God.

And so, we sacrifice for one another.

We forgive one another.

We turn always away from violence.

We seek never to dominate.

Love one another, and love the God in whose image you are most wonderfully made.