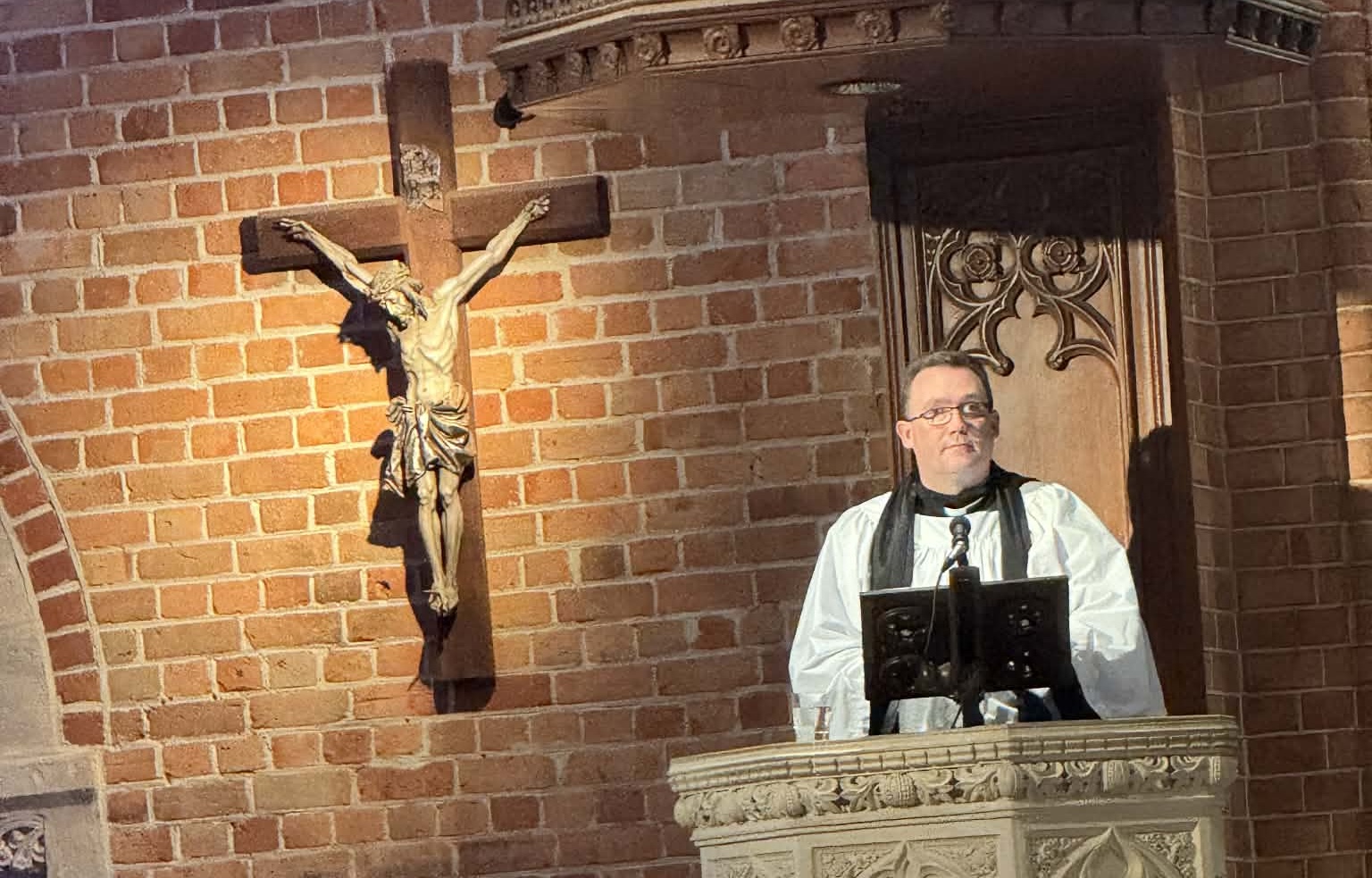

This sermon was preached on the 18th of Januery 2026, The Second Sunday after Epiphany, in Saint George’s Cathedral, Perth.

Texts:

“The one who is righteous will live by faith.” (Rom 1.17b quoting Hab 2.4b)

Those words link the two readings we have just heard from the Bible.

They are the words of the prophet Habakkuk, quoted by Saint Paul in his letter to the Romans. And I can almost picture those words on the side of a coffee mug, rendered in a colourful, swirly, italicised font, maybe beside a garish depiction of a sunrise.

Taken directly, this phrase from the Bible, from the words of Habakkuk, can sound very trite indeed. Don’t worry about what you see around you. Don’t worry about the injustice that you see everywhere you look. Just live by faith.

Don’t worry about the news you hear day by day of powers and principalities, nations and the empires, at work conquering and killing, and finally excusing it all with tales of their own righteousness.

And certainly don’t ask yourself that dread question: if God is good, if God is really, truly Good, then why is there so much evil in the world? Why does evil in all of its shapes – greed, avarice, idolatry – why does evil seem to flourish, why is evil seemingly rewarded?

Don’t worry, have faith. Let go of justice, close your eyes, and trust.

And if you should slip up, if you slip up and open your eyes again, and witness what seems to be evil, boldly rampant, then be reassured. God is directly in charge, and God is a judge both active and swift. Punishment follows transgression. And so you can be certain that there is no such thing as oppression, there is no such thing as injustice: there is only God’s rule, God’s justice.

What an awful vision of the Divine, of God, that is. And I have taken it to its limits – just as Habakkuk did in his time.

Judea was attacked by the Chaldeans. Jerusalem and its temple were destroyed. Precious human lives were ended, the people of a nation were scattered. The horrors of war were visited upon the innocent. Was this God’s punishment, God’s justice, God’s consequence for the sin of Judea?

That would be a convenient answer, wouldn’t it? It would allow the understanding of God as always good, always righteous, always in charge, to survive even the destruction of the homeland of God’s people, and their death in thousands and tens of thousands.

But Habakkuk protests.

He protests the violence of the Chaldeans, the avarice of empire, and God’s apparent utilisation of the wicked. These are his words:

“Why do you look on the treacherous, and [yet] are silent when the wicked swallow those more righteous than they?” (Hab 1.13b)

In our own time, in this century, the international order that emerged after the Second World War, flawed and tenuous as it ever was, is under serious threat. It seems that we are returning to a consensus that the mighty nations of the world can take whatever they desire, as if by right.

Surely, that is a fearful prospect. It is a return to the time of Habakkuk; a return also to the time of the earthly ministry of Jesus, when empires vied for power, thinking themselves great.

And where is God in that?

“I will stand at my watchpost and station myself on the rampart. I will keep watch to see what [God] will say to me, and what [God] will answer concerning my complaint.” (Hab 2.1)

The prophecy of Habakkuk never answers its own complaint. Habakkuk never explains away the presence of evil and injustice in the world, in conflict with the goodness of God.

Instead, Habakkuk protests. He protests to the world, to his kin, and most profoundly of all, he protests to God.

And this is faith, truly expressed. Not in trite, comforting sayings, not in the closing of one’s eyes in the face of injustice, but in boldly taking up one’s place at the watchpost, and waiting to see God at work.

There is evil in the world. There are powers and principalities, there are even those who would take up the Holy Name of Jesus and make it into an idol, an excuse for their vanity and folly, for their violence upon their fellow person.

But remember the Good News. Remember the life of Jesus: remember his protest against empire, against exploitation, against injustice.

God came among us not with excuses, not with trite sayings, but with words and deeds which held up a mirror to human iniquity. God came among us with protest. Habakkuk’s complaint, our complaint, finds its origin in God’s complaint.

Jesus taught us and loved us that we might be restored, that we might let go of self-worship and return to God.

And we killed him for it. We killed him in the most degrading, violent, shameful way imaginable. But like Saint Paul, I am not ashamed of the death of Jesus upon the Cross, the scandal of the Gospel. And you should not be ashamed either.

Upon the Cross, Jesus took upon himself the worst that human beings can do to one another, the sum of our violence; the totality of our sin; the final, embodied expression of our rejection of God. And he died.

If God’s justice, if God’s cosmic rule worked along the lines of human justice, the world would have died with him. Humanity would have been blotted out. But that was not the reply of God. God replied with life – life eternal. How great the mystery of God’s justice is!

I started this sermon with Saint Paul’s quotation from the words of Habakkuk:

“The one who is righteous will live by faith.”

Well, those words can be translated another way.

“The one who is righteous through faith will live.”

The witness of Habakkuk, and the witness of Jesus, is that true faith requires protest. True faith forgoes easy answers. Protest lies at the heart of faith. Protest leads us into the mystery of God’s goodness.

And so, my charge for you today is to struggle. Struggle with the injustice you witness, protest it. Lend your body to that protest.

Take your place at the watchpost.

Answer the duty of your baptism.

Never be ashamed of the Gospel.

“The one who is righteous, through faith will live.”

Amen.